Where I Work

Click on an area to find out more.

(Please be patient - this part of my website is under development!)

Click on an area to find out more.

(Please be patient - this part of my website is under development!)

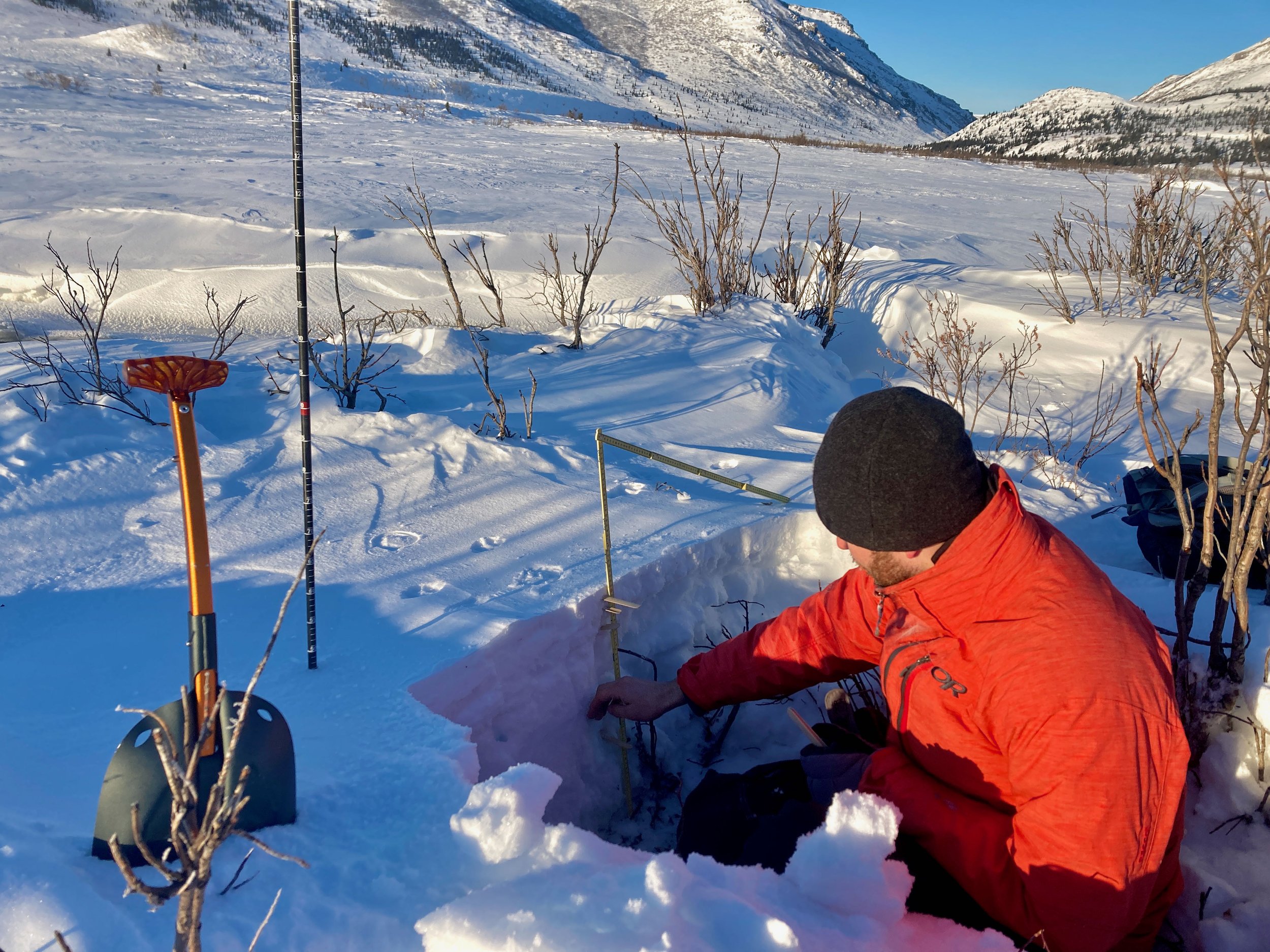

My current PhD project uses intensive fieldwork in both Alaska and Washington to explore the relationship between snow and predator-prey dynamics. My research is through the Prugh Lab at the University of Washington’s School of Environmental and Forest Sciences. Read more at http://www.prughlab.com/ or check out our first snow-wildlife paper at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/oik.09925.

My current PhD project uses intensive fieldwork in both Alaska and Washington to explore the relationship between snow and predator-prey dynamics. My research is through the Prugh Lab at the University of Washington’s School of Environmental and Forest Sciences. Read more at http://www.prughlab.com/ or check out our first snow-wildlife paper at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/oik.09925.

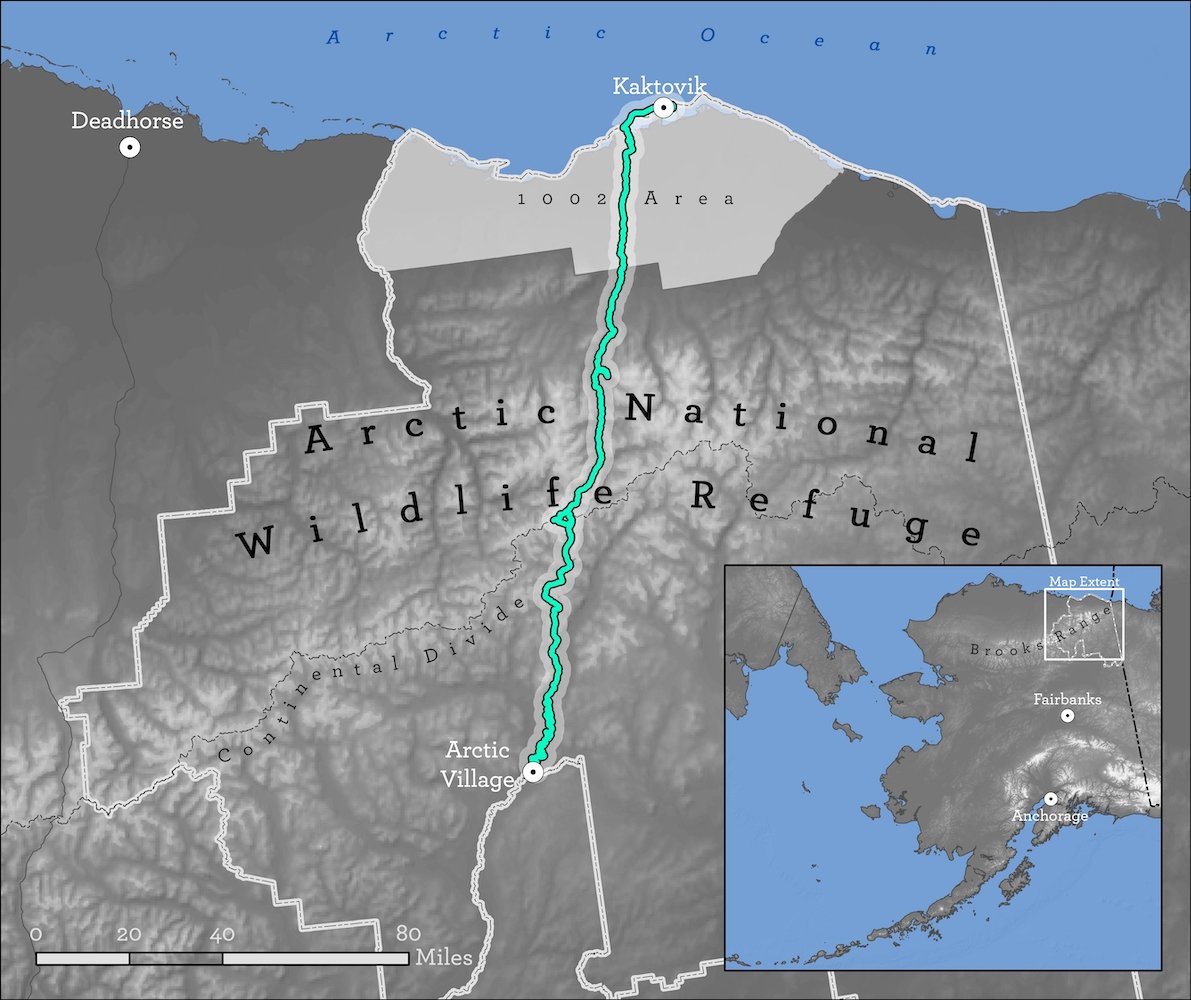

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge harbors the calving grounds for the 200,000-strong Porcupine Caribou Herd, but has been the subject of decades of industry interest in exploring for oil and gas resources. This place is near and dear to me: I got to traverse the Refuge and join in on the American Packrafting Association’s activism efforts, writing up some of my experiences in this blog series here: https://www.kickstepapproaches.com/stories/refuge-traverse-1.

One of my first projects as Kickstep Approaches involved taking a closer look at oil exploration-related disturbances to denning polar bears (via seismic lines and infrared den detection). My findings directly resulted in revisions to the official impact assessments: https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.21800 and https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.21889.

The National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (NPR-A) comprises 23 million acres of prime habitat for caribou and migratory birds. Massive oil extraction operations and associated infrastructure continue to expand into previously wild areas. In addition to simulation modeling to assess likely impacts from oil and gas development (https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3530), I help Alaska’s conservation coalition keep track of where oil and gas projects are happening in relation to key wildlife values. Learn more at: https://alaskawild.org/reserve/.

Photo credit: Thor Lindstam, thorlindstam.com

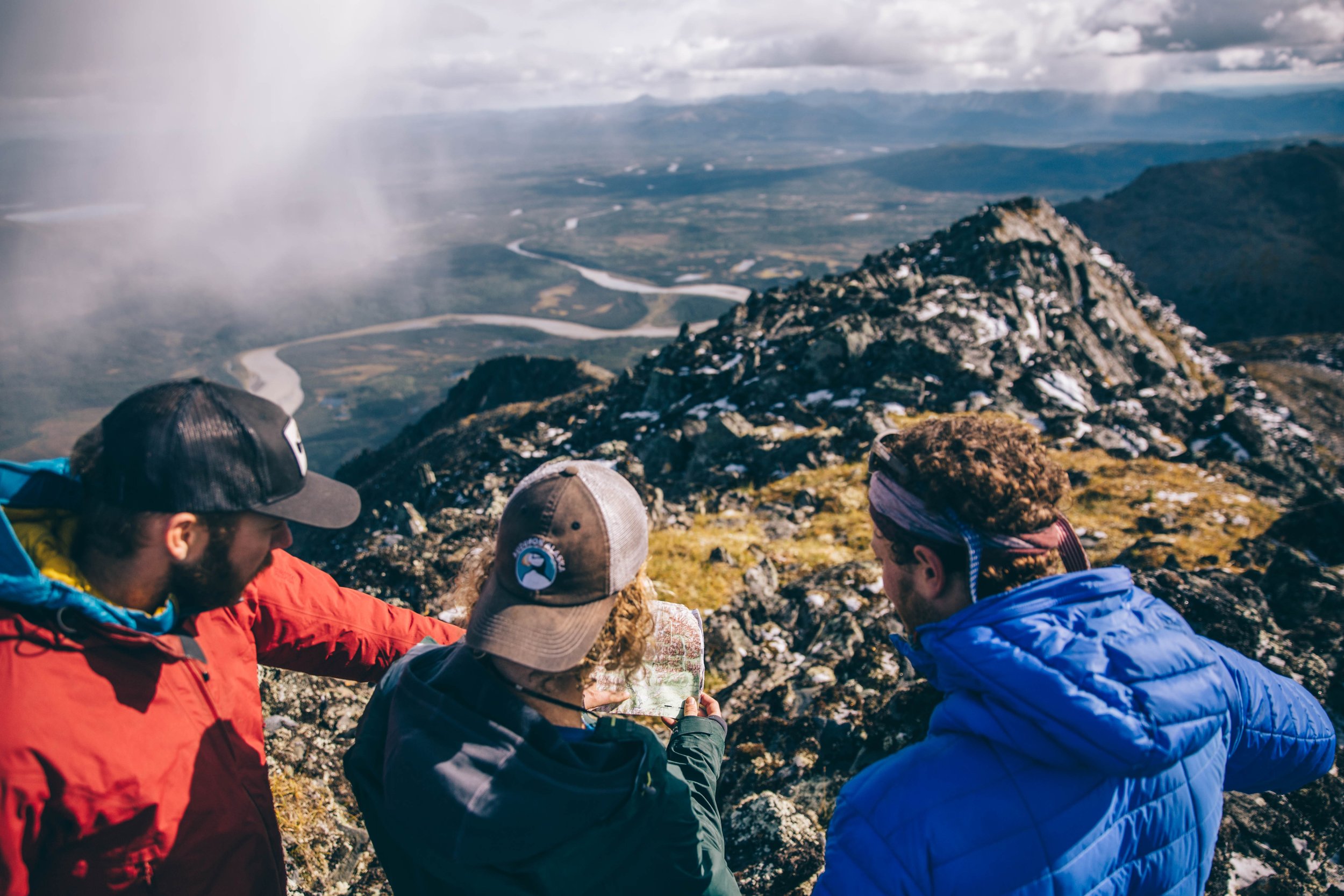

The proposed Ambler Road threatens to bisect connectivity, for wildlife and recreationists alike, through one of the largest blocks of continuous wilderness in the United States. In addition to providing recorded testimony during the formal NEPA process, I’ve been fortunate to be able to paddle through many areas directly on the chopping block in Gates of the Arctic National Park. Learn more here: https://northexposurestudios.com/paving-tundra.

Photo: Andy Cochrane

Known as “the birthplace of the winds” to the Aleut people, the Aleutian Islands follow through on their reputation. This beautiful - and yes, windswept - chain of volcanoes holds a prominent position both for marine wildlife and for international commerce.

Recent conservation efforts helped reroute large vessels to safer passages, but relied on entirely voluntary measures to do so, without much threat of enforcement. So did ships actually follow the new routes? You bet.

I led a peer-reviewed study showing that when insurance, conservation groups, and maritime experts convene, everyone wins. Read our study here: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.579905.

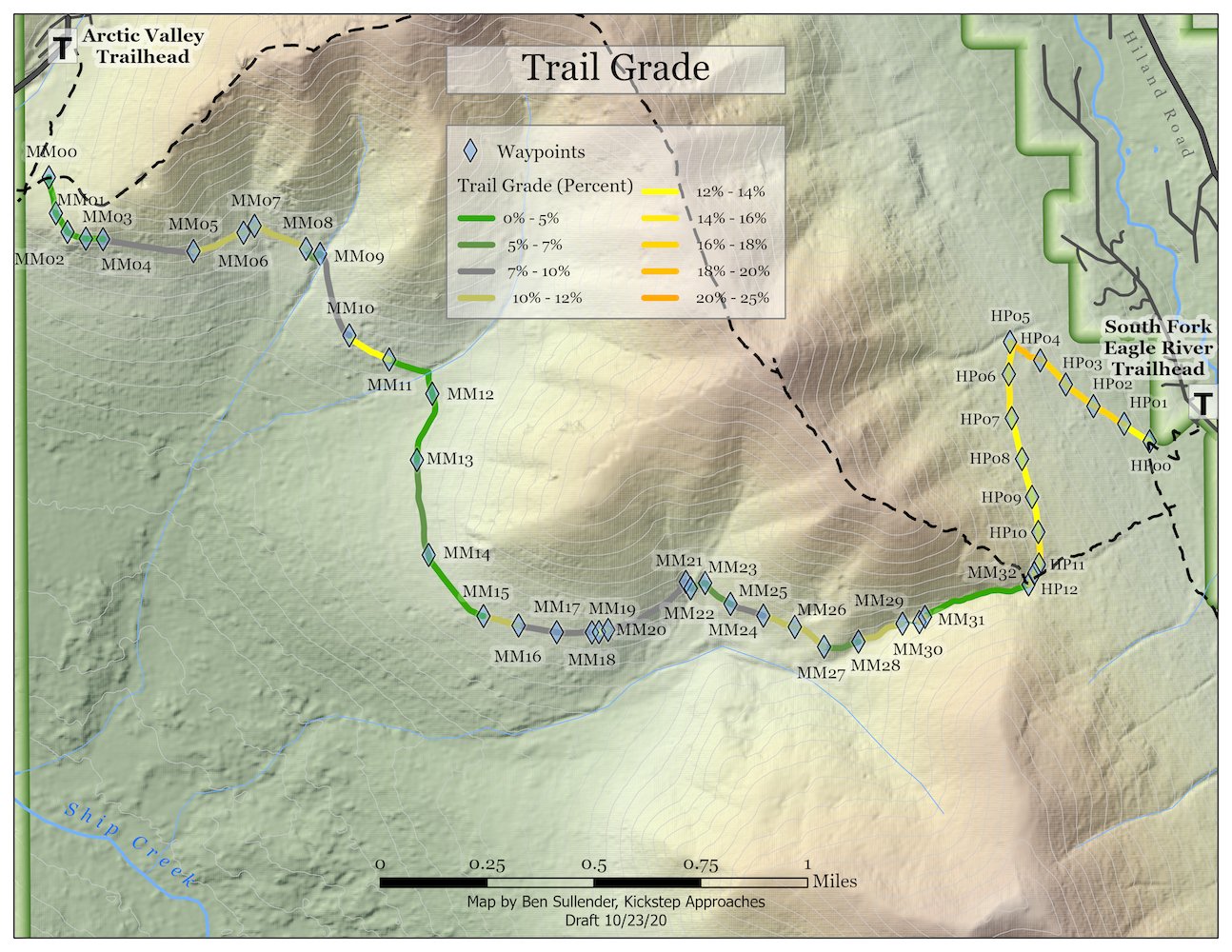

Chugach State Park is the most-visited public land in the entire state of Alaska, hosting about 1.5 million hikers, bikers, skiers, hunters, anglers, rock climbers, and paddlers per year. (Denali National Park, by comparison, has about 600,000 visitors/year.) Outdoor recreation has exploded in popularity in recent years, with full trailhead parking lots and crowded trails becoming the norm. Sprawling social paths in heavily used areas, particularly in fragile alpine tundra, can permanently damage otherwise valuable wildlife habitat, as well as creating unsightly, muddy scars that are as hard on the legs as they are on the eyes. Concentrating some of this foot- (and horse- and bike- and ATV-) traffic onto purpose-built trails allows recreationists to travel these landscapes while minimizing damage.

In 2020, I helped Alaska Trails and the Student Conservation Association survey and map the Muktuk Marston Memorial Trail, connecting two major hiking areas and formalizing a social path. As the exciting 500-mile Alaska Traverse (formerly called the Alaska Long Trail) takes shape, I hope to stay engaged with the recreation community to help chart a sustainable future for exploring our great state.

Read more here: https://alaskacf.org/funds/muktuk-marston-hunter-pass-trail/ and https://www.alaska-trails.org/alaska-traverse.

Migratory wildlife travel huge distances to connect a network of areas where they can find food, safe harbor, or both. Marine mammals, in particular, frequently rely on recurring “hotspots,” where bathymetry, prevailing currents, freshwater influx, and other physical processes concentrate biological productivity. By analyzing wildlife tracking data and seasonal factors such as sea-ice dynamics, we can locate these “hotspots” in space and time even as climate change reshuffles entire ecosystems. Some of my spatial ecology work has supported WWF’s groundbreaking global conservation efforts such as ArcNet (https://www.worldwildlife.org/projects/arcnet-protecting-marine-biodiversity-in-the-arctic) and Arctic Blue Corridors (https://www.arcticwwf.org/our-priorities/nature/arctic-blue-corridors/).